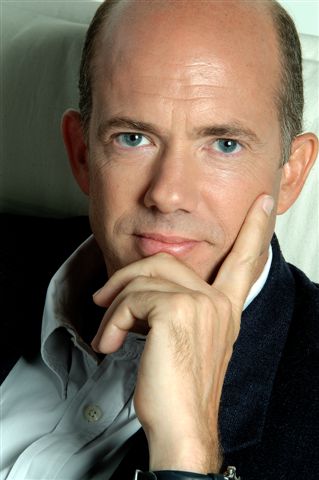

Continuing the conversation on methodology in economics recently in Neoclassical Theory under Fire from the Sciences, followed up with David Altig Deflates Ball, a conversation in which many of you expressed doubt about the usefulness of formal economic models, here's Paul Krugman with rebuttal to your arguments:

Two Cheers for Formalism, by Paul Krugman: Attacks on the excessive formalism of economics - on its reliance on abstract models, on its use of too much mathematics - have been a constant for the past 150 years. Some of those attacks have come from knowledgeable insiders - from the likes of McCloskey (1997) or even Marshall. More often, however, the attacks have come from outsiders - from journalists, political crusaders, and so on.

In this essay I want to make three points. First, much of the criticism of formalism in economics is an attack on a straw man: the reality of what good economists do is a lot less formalistic than the popular image. Bad economists, of course, do bad economics; but one should not confuse a complaint about quality with a complaint about methodology. Second, when outsiders criticize formalism in economics, their real complaint is often not about method but about content - in particular, they dislike "formalistic" arguments not because they are formalistic, but because they refute their pet doctrines. Finally, as a practical matter formalism is crucial to progress in economic thought - even when it turns out that the ideas initially developed with the help of formal analysis can in the end, with some work, be expressed in plain English. Moreover, this is especially true precisely in the sorts of areas that economists are often accused of neglecting, such as those that involve imperfect competition, incomplete rationality, and so on.

1. What do economists do?

A few years ago a more or less typical article about the plight of economics (Parker 1993) criticized economists for "their deductive method, their formalism, their over-reliance on arcane algebra, their imperviousness to complex evidence", and repeatedly charged the field both with an excessive faith in free markets and with irrelevance. These accusations are standard. But are they really the way economics is? Do they really describe the way economists do economics?

Clearly each piece of this critique describes at least some economists. There are economists who rely on a "deductive method" - although if this is supposed to mean deriving everything from predetermined axioms rather than building models suggested by real-world observations, it actually describes only a handful of practitioners. "Formalism" could mean many things; so let's hold off on that one. "Over-reliance on arcane algebra" - well, there is certainly a lot of algebra in economics, and some of it is surely excessive. "Imperviousness to complex evidence" - actually, that is probably dead wrong. The real problem with the parts of economics that I personally believe have gone off the rails, such as much of business cycle theory, is imperviousness to simple evidence. But that, as we will see, is by no means a problem unique to mainstream economists.

But while some economists must fit each of this descriptions, do many leading economists fit all of them? And is irrelevance a major problem with contemporary economics?

Here is a simple reality check. The American Economic Association's John Bates Clark Medal is a highly coveted award; it is therefore an indicator of what the profession values. And because it must be given to an economist under 40, it reflects research undertaken fairly recently. So what do we learn about the values of the profession - the sorts of work that command the highest rewards - by looking at, say, the last ten Clark Medalists? Here is the list: 1979, A. Michael Spence; 1981, Joseph Stiglitz; 1983, James Heckman; 1985, Jerry Hausman; 1987, Sanford Grossman; 1989, David Kreps; 1991, yours truly; 1993, Lawrence Summers; 1995, David Card; 1997, Kevin Murphy. In short: two middlebrow theorists whose work on imperfect markets has had major impact both on policy and on corporate strategy; two econometricians whose techniques are widely used in practical applications; two theorists who specialized on issues of information and uncertainty; a trade theorist who focussed on increasing returns and imperfect competition; a macroeconomist with a strong empirical and policy bent; and two very empirically-oriented labor economists. Not one of these economists has worked mainly on perfectly competitive markets, or is a free-market ideologue. And as far as relevance goes, notice that in their subsequent careers some members of the group have found that businesses and governments are willing to pay large sums for work based on their earlier research; one became Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, while another is now a very powerful Deputy Treasury Secretary; and one has been known to write reasonably successfully for non-economists. So where in this group is the excessive formalism, the excessive reliance on the deductive method, of which economists are routinely accused?

You may answer that while the very best economists may be free of the sins for which the profession is criticized, things are different once one goes down the scale. But take any of the fields in which one of the lucky 10 works, and try listing 5 or 10 other successful economists in the same area. How many of them are engaged in arcane algebra that has no relationship to reality? (Some of them, like auction theorists or finance theorists, are indeed engaged in arcane algebra - but it turns out to be very relevant indeed). I have not done this exercise, but I would guess that if one took the 100 economists most cited in the Social Science Citation Index and summarized the nature of their work, it would turn out to be mostly focussed either on real-world problems, or on techniques that other economists have found very useful in addressing real-world problems. So where does the picture of economists as a tribe engaged in pointless, abstract mathematical games come from?

Perhaps the picture is based on the fact that most economists do not do first-rate research, and that there is a lot of irrelevant mathematical modeling out there. But in what academic field do most people do first-rate research? And if someone is doing work that will not be read or cited, does it matter whether it is boring literary work (as in many humanities), boring experimental work (as in many physical sciences), or boring mathematical modeling?

One can make a good case that the intellectual level of economics is not as high as it should be, given the importance of the subject. But that is a complaint about quality, not formalism. What, then, leads to such angry charges of excessive formalism?

2. Why outsiders dislike economic "formalism"

In 1997 the editor of Governing magazine published an op-ed attacking the economics profession for denying the obvious fact that globalization was having devastating effects on the economy (Ehrenhalt 1997). As an example of just how bad economists are, he quoted an unnamed "prominent economist" (the reference was actually to Krugman 1996), who had written that "there are ... important ideas in economics that are crystal clear if you can stand algebra, and very difficult to grasp if you can't". This, according to the op-ed writer, was an "insult", a "charge of illiteracy"; he went on to assert that algebra could not be essential to economic understanding, because if it were this would delegitimize the opinions of people who had not studied algebra when young and were now too old to retool.

It hardly gets clearer than this. Many, indeed probably most, of the non-economists who attack the field's formalism do so not because that formalism makes the field irrelevant, but on the contrary because economists insist that their equations actually do say something about the real world. And since the critic's view conflicts with what the equations say, this whole business of using mathematics to think about economics must be a bad thing.

What sort of equations are we talking about here? Well, how about the equation that says that the sum of a nation's capital account and current account is zero?

This is not meant to be a joke. While a number of issues motivate outsider critics of the economics profession, surely the most prominent and emotional involves concerns about the impact of globalization. Many people (like the op-ed writer cited above) who regard themselves as knowledgeable about economic affairs are convinced that growing international trade and investment are bad things for workers everywhere. The typical story - as found, for example, in the 1994 World Competitiveness Report (World Economic Forum 1994) or in Greider (1997a) - goes like this: Multinational corporations and other investors are massively relocating capital to low-wage countries, undermining traditional employment in the advanced countries. Meanwhile, hopes that these newly industrializing economies will provide export opportunities and thus alternative jobs for the displaced workers are a mirage: wages and hence purchasing power in these countries will remain low, both because of the sheer size of their labor forces and because they need to keep wages low to attract a continuing inflow of capital. Thus workers in the Third World will see no benefit from the process - their economies will achieve high productivity while continuing to pay low wages - while those in advanced countries will find their position undermined both by trade deficits and by capital outflows.

What is wrong with this story? Economists quickly notice that it violates the equation that says that current account plus capital account equals zero. It cannot be true that newly industrializing economies are or will be the recipients of large capital inflows and at the same time export much more than they are importing. And once one tries to fix this aspect of the story, the whole thing falls apart. In particular, suppose that one decides that newly industrializing economies will, in fact, attract large capital inflows. Then one must conclude that they will run current account and probably trade deficits rather than surpluses. But how can they run trade deficits when their productivity rises but their wages remain low? Doesn't this cost advantage ensure a trade surplus? Well, something must be wrong with the premise; perhaps wages will not remain low after all.

One can immediately see the reason why people hate economists. Here is a compelling, powerful story about the world economy, one that dovetails with the political agenda of those who tell it, and is a clear call to action. Yet economists insist that the story is literally nonsense - that it is, in the physicist Wolfgang Pauli's phrase, "not even wrong" - because of an abstract equation. Here, surely, is a prime example of how formalism makes economists impervious to the evidence.

The trouble is that the economists are right. The popular story is literally nonsense: that crucial equation is not some abstract theory, it is a simple accounting identity - and there is no way to save the story while getting the accounting right. Moreover, the facts fit the economist's story quite well. Most newly industrializing economies run trade and current account deficits, not surpluses: of the 25 "emerging market" economies listed at the back of The Economist, 17 were running trade deficits when this essay was written, 20 current account deficits. And wages in rapidly industrializing economies have not stayed low, they have risen sharply: the U.S. Labor Department's index of compensation in newly industrializing Asia rose from 8 percent of the US level in 1975 to 32 percent in 1995. (Incidentally, the response of opponents of globalization when these facts were pointed out helps put their charge that economists are "impervious to complex evidence" in perspective. Greider (1997b), offered an opportunity to rebut questions about his thesis, simply ignored the contrary evidence and repeated his original assertions without alteration. And other critics of conventional economic views about globalization, like the Economic Policy Institute, did not disavow Greider or express regret that he had failed to check his facts; they leapt to his defense, attempting to rationalize his claims).

This is not an incidental or unusual example. The refusal of economists to accept the popular indictment of globalization is, to repeat, the most important reason for attacks on the profession in recent years. Indeed, that op-ed was probably motivated specifically by the negative reviews Greider's book had received from economists. And thus this story helps reveal what the outsider critics really mean by their critique. By "formalism" they do not mean differential topology or fixed-point theorems: they mean annoying insistence on adding-up constraints, or such abstruse arguments as the assertion that partial equilibrium reasoning (increased productivity in a given industry may well lower employment in that same industry) does not always carry over to general equilibrium (increased productivity in the economy as a whole is much less likely to reduce employment in the economy as a whole).

A final point on the outsider critics: economists rarely listen seriously to what these critics are actually saying. The normal impulse is to assume that complaints from outsiders are simply a stronger version of the sorts of things economists criticize in each other. An economist like Rodrik (1997), whose argument that the adverse effects of globalization are larger than most of the rest of us believe has received enthusiastic approbation from critics of economics, seems himself to believe that someone like Greider is far out on the fringe of the debate, and not even worth arguing with. The truth, however, is that when critics attack formalism in economics what they really mean is the infuriating insistence of economists that they mind their arithmetic; and the reason they like Rodrik's work is precisely that they believe that it validates the ideas of people like Greider.

3. Was Marshall right?

McCloskey (1997) has recently make an eloquent appeal for a return to a "Marshallian" style of economic discourse: a style based on verbal, intuitive exposition rather than formal modeling. Marshall (quoted in Sills and Merton 1991, p. 151) himself, of course, famously described his method:

(1) Use mathematics as a shorthand language, rather than as an engine of inquiry. (2) Keep to them till you have done. (3) Translate into English. (4) Then illustrate by examples that are important in real life. (5) Burn the mathematics. (6) If you can't succeed in 4, burn 3.

Was he right? Marshall's dictum can usefully be divided into two parts: how one should arrive at an economic idea, and how one should communicate it.

Should one use mathematics as an "engine of inquiry"? This is actually an ambiguous phrase. It might mean getting one's ideas entirely from mathematical logic; if so, that is a practice very few economists engage in. What is true, however, is that many economists use mathematics not merely as a way to check the internal consistency of their ideas, but as an "intuition pump"; they start with a vaguely formulated idea, try to build a model that conveys that idea, and allow the developing model in turn to alter their intuitions. One way to interpret what Marshall was saying, then, is that one should avoid this process - one should use mathematics only to check intuitions, never to help develop them.

What was Marshall thinking of when he said this (if that was what he meant to say)? Probably he had in mind his own youthful explorations of general-equilibrium trade theory, and in particular his development of the offer-curve technique for analyzing the determination of the terms of trade. (Irwin 1996, pp. 110-111 describes Marshall's ambivalence regarding his own creation). Offer-curve analysis, it turned out, forces one to a conclusion that the modeler might not have expected or wanted: a large country, with the ability to affect world prices, can always raise its real income by imposing a small tariff. Marshall's sense was that this conclusion, however much it might be a necessary consequence of the mathematical logic, was wrong or at least unimportant as a practical matter, and presumably this experience was what led him to conclude that one should only use math to check conclusions, not to arrive at them.

And yet general-equilibrium trade analysis is one of those areas in which models are a crucial aid to intuition. Consider once again the questions posed by the rise of newly industrializing economies. The common perception of most people who think about the issue at all is that the emergence of new competitors must surely reduce real incomes in the established economies - indeed, that this has already happened. On the other hand, some business enthusiasts are quite sure that the expansion of world markets will bring vast prosperity to everyone. Thanks to the models of Hicks (1953) and especially Johnson (1955) well-trained economists eventually learn why both intuitions are deeply wrong. Growth in other countries can either help or hurt us: it depends on the effect on our terms of trade, an effect that in turn depends on the bias of that growth. (And as a quantitative, empirical matter the overall effects are very small, both because North-South trade is a small share of Northern income and because there have not been large movements in the terms of trade). This position can eventually be made to seem intuitive, but it would have been very hard to arrive at without the aid of models - in particular, without the aid of Marshall's offer-curve construction.

This is not an isolated example. It is crucially important in itself, and it is also representative. Most of the topics on which economists hold views that are both different from "common sense" and unambiguously closer to the truth than popular beliefs involve some form of adding-up constraint, indirect chain of causation, feedback effect, etc.. Why can economists keep such things straight when even highly intelligent non-economists cannot? Because they have used mathematical models to help focus and form their intuition.

Of course, this gain in intuition sometimes comes at a cost: the modeler can become a prisoner of the assumptions embodied in his model. One often hears accusations, in particular, that model-based economics inevitably biases the field toward standard economic assumptions like constant returns, perfect competition, and perfect information. Yet this need not be true. In fact, economists like myself (and many of the others on that list of Clark winners) who have worked at length on imperfect markets have found modeling an essential discipline in the process of exploring new territory.

Trade theory is again a case in point. By the late 1970s there had been decades of discontent with conventional trade theory - discontent often manifested by complaints that conventional theory neglected increasing returns and imperfect competition. Many manifestos denouncing the conventional views had been published. Yet in all that literature of discontent it is hard to find any clear, let alone useful ideas. Only when the "new trade theory" began to emerge, driven by mathematical models that both embodied and shaped intuition, did compelling new ways of looking at international trade actually take shape.

Still, while it may be a good idea to use mathematical models to help develop one's ideas, shouldn't one then follow Marshall's precepts in communicating those ideas? The answer, surely, is that it depends on the audience. Marshall's advice is exactly appropriate when an economist is writing for an intelligent, literate audience of non-economists - such as, say, the readers of Foreign Affairs or Slate. To reach such an audience, to help them get a grasp of some important economic point (like the reasons why economic growth in Asia is not a disaster for the West), it is essential to find a way to express the crucial ideas without the formal apparatus. Nor is this a demeaning exercise: on the contrary, finding a way to convey good economic reasoning without the usual equations and jargon can be both a valuable discipline and an exhilarating experience. And even professional economists, especially those who specialize in different areas, can find non-technical expositions of economic concepts very useful.

But professional economists also have another task: to communicate with each other, and in so doing to help economics as a discipline progress. In this task it is important for your colleagues (and students) to understand how you arrived at your conclusions, partly so that they can look for weak points, partly so that they may find other uses for the technical tricks you used to think an issue through. I like to think that I can manage to explain international economic concepts pretty convincingly to a broader public without ever drawing an offer curve; I can give a pretty good account of the "home market effect" on trade patterns without ever mentioning Dixit-Stiglitz monopolistic competition and iceberg transport costs. However, I would be doing my graduate students a grave disservice if I never taught them offer curves and Dixit-Stiglitz-iceberg trade models: the point of their education is to learn methods, not answers. And publication in professional journals is or at least should be a form of education: it is how economists teach each other about their work. Tjalling Koopmans (1957) once complained about Marshall's "diplomatic style" - his emphasis on persuasion, his mingling of theory and evidence, his willingness to sweep awkward points under the rug. I am a great admirer of Marshall, yet Koopmans had a point. Marshall's style - the style some insider critics think we need to recapture - was entirely appropriate for a general audience, even a highly educated and intellectual one. But Marshall adopted the same style when writing for economists and their students. To do so is in effect to turn professional economics into the repetition of received truths rather than a continual process of exploration. Indeed, one can do no better on this than to quote Marshall again:

"Economic doctrine ... is not a body of concrete truth, but an engine for the discovery of concrete truth ..." (quoted in Sills and Merton, p. 150).

How are students and colleagues supposed to learn how to use this engine if you burn the evidence of the engine at work?

What, then, is left of the accusation of excessive formalism in economics? Perhaps the moral should be that there are not enough economists doing what Marshall did: writing economics in a way that makes it accessible and persuasive to a broader, though hardly mass, audience. I have spoken of the style appropriate for publications like Foreign Affairs; yet this is very nearly an abstract speculation. How many good economists actually do write carefully constructed, well-targeted articles, based on serious economic analysis, for a wider audience? I believe that the number in the United States can be counted on the fingers of one hand. This is absurdly low given both the size of the profession and the stakes involved: such articles, together with non-technical books aimed at a broader audience, can sometimes exert a startling influence on public discussion and even on policy. Yet for the most part good economists have simply abandoned this kind of writing, leaving the field wide open for the sort of person who hates economists because they insist that his arguments add up.

Here, then, is a revised version of Marshall's rules:

(1) Figure out what you think about an issue, working back and forth among verbal intuition, evidence, and as much math as you need. (2) Stay with it till you are done. (3) Publish the intuition, the math, and the evidence - all three - in an economics journal. (4) But also try to find a way of expressing the idea without the formal apparatus. (5) If you can, publish that where it can do the world some good.

In short, two cheers for formalism - but reserve the third for sophisticated informality.

REFERENCES

Ehrenhalt, A. (1997), "Keepers of the dismal faith", The New York Times, Feb. 23.

Greider, W. (1997a), One World, Ready or Not: The Manic Logic of Global Capitalism, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Greider, W. (1997b), "When optimism meets overcapacity", The New York Times, Oct. 13.

Hicks, J.R. (1953), "The long-run dollar problem", Oxford Economic Papers 2:117-135.

Irwin, D. (1996), Against theTide: An Intellectual History of Free Trade, Princeton University Press.

Johnson, H. (1955), "Economic expansion and international trade", Manchester School of Social and Economic Studies 23:95-112.

Koopmans, T. (1957), Three Essays on the State of Economic Science, New York:McGraw-Hill.

Krugman, P. (1996), "Economic culture wars", Slate, Oct. 24.

McCloskey, D. (1997), The Vices of Economics: The Virtues of the Bourgeoisie, Amsterdam University Press.

Parker, R. (1993), "Can economists save economics?", The American Prospect, 13.

Rodrik, D. (1997) Has Globalization Gone too Far?, Washington: Institute for International Economics.

Sills, D. and Merton, R. (1991), International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, vol. 19 (Social Science Quotations), New York: Macmillan.

World Economic Forum (1994), The World Competitiveness Report 1994.